Winter Walks

Looking for Fungi in the Snow with Hank

Good evening, friends,

When I worked in Central Park, we had a fourteen-day streak in 2018 where the temperature never rose above freezing. On days like those, my colleagues at the park would come in and say “it’s dumb brick out there” and I, their twenty-three-year-old coworker from Connecticut, would respond “yeah.”

Well, dumb brick it was again this past week. I teased it in the last newsletter, but I spent the week dog-sitting, so Hank and I would routinely bundle up and set out to see what fungi we could find in the frozen New England woods. Hank is the type of dog who likes to be your shadow. If I sit on the couch, he gets on the couch. If I get up and go downstairs, he gets up and goes downstairs. If I want to go find fungi in the woods, he follows in my bootprints or even pounces ahead to break trail.

Most of the fungi we found were aerial and growing on dead wood or on standing trees. Hank did some digging in the snow, and I’m not sure if he ever found what he was looking for, but my preference was to let buried logs lie. Nonetheless, we came away with some insightful fungal finds and some interesting non-fungal winter observations as well.

The Fungal

Black Knot (Apiosporina morbosa)

When the woods thaw and spring rains begin, these blackberry-like fruiting bodies split open and eject the spores of this pathogenic fungus. The airborne spores will hope to land on another black cherry (Prunus serotina), or any other species of cherry for that matter. The spores that find a Prunus landing pad will germinate in a following rain, enter the plant at the node (where a leaf or branch comes out), and the fungus begins to form a gall in the wood. The gall grows larger year after year, producing those black fruiting bodies seen above, and eventually gets to a size where it completely chokes out the branch.

I wrote about A. morbosa here.

Sarea resinae / Zythia resinae

These incredibly small, orange cups are the fruiting bodies of a resinicolous fungus. A fungus that grows on conifer resin. Resin is incredibly antifungal and antibacterial (which makes sense since the tree secretes it to help seal wounds), but impressively these fungi have found a sticky little home here. Although other than living on/in resin, the lifestyle of the fungus isn’t well understood and it’s not definite that the fungus consumes the resin. When I originally wrote about these last spring, Roz Lowen noted that Sarea resinae, not Zythia resinae, is the name recognized by Index Fungorum.

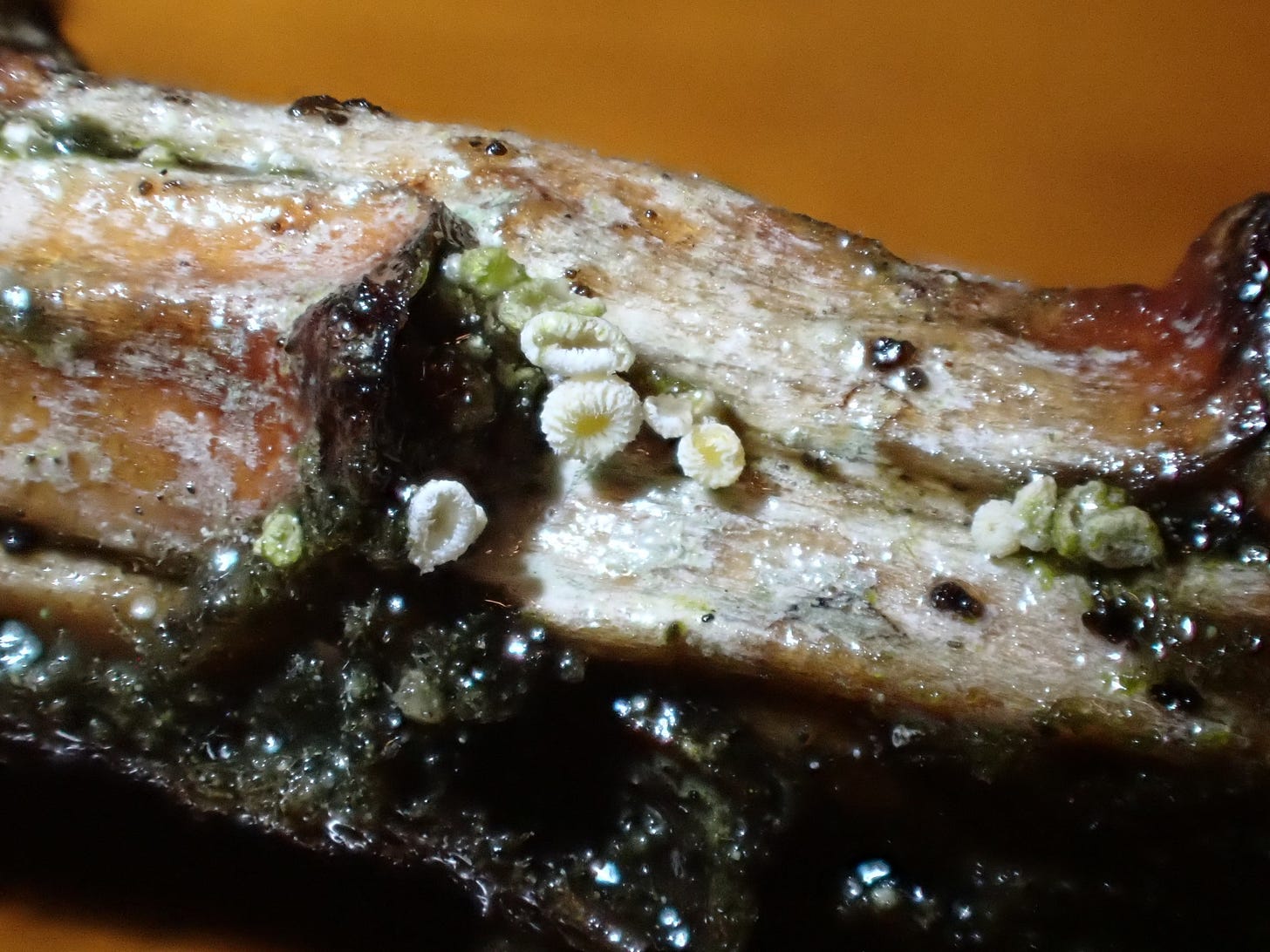

Lachnellula sp. ?

Despite all the snow on the ground, the air is quite dry, and so were these crusty cups which we found growing on a dead pitch pine branch. I got a little tip from Jan Thornhill’s blog, which was to stick the branch in warm water to rehydrate the fungi, and they did perk up a bit. She noted that while they occasionally can be found growing directly from conifer wood, they’re more often found growing out of resin.

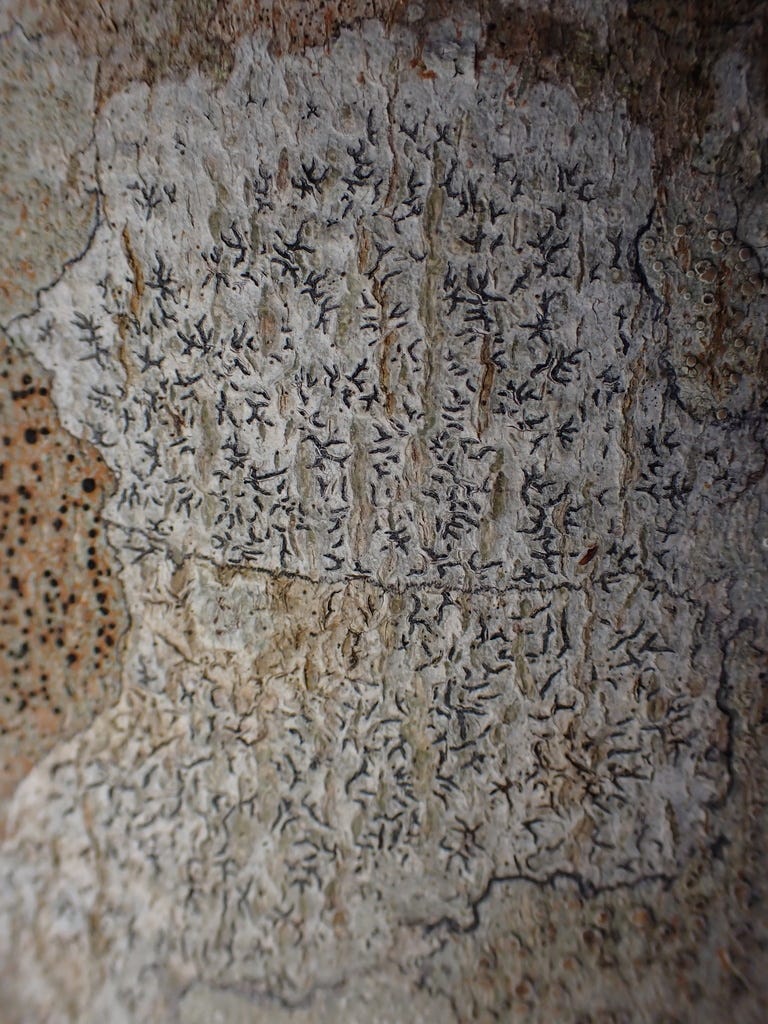

Lichen

When all else is buried in the snow, you can always turn to the lichen on tree bark. There are a couple different species of lichen in just the picture above. The dark line near the top of the branch separates two species, and you can also directly compare the different apothecia — the cup-shaped reproductive structures of the mycobiont (the fungal partner in the lichen). Believe it or not, there are over 300 species in the genus Lecanora (Reference 1). If you’ve been looking for something to keep you busy this winter, look no further.

My favorite lichen fact is that in certain species of lichen, the fungus will partner with a different species of algae relative to where they are in the world. A fungus in a northerly latitude will partner with an algae better adapted to cold environments, whereas one in the tropics will find a warm-weather photobiont (the photosynthetic partner in the lichen). A runner-up fact would be that one lichen can have multiple different fungal species living within them.

COMA Presentation

If you’ve enjoyed reading about winter fungi, then you’ll really have a ball this Thursday at the Friends Meetinghouse in West Harrison, NY where I will present on Winter Fungi of the Northeast to the Connecticut-Westchester Mycological Association (COMA). Full details below.

Winter Fungi of the Northeast will be presented by Aubrey Carter on Thursday, February 12, at the Friends Meetinghouse, 4455 Purchase Street, West Harrison, NY. Doors open at 7PM, and the program will start promptly at 7:30. The event is open to all, including non-members, but PLEASE NOTE: Registration is required for this event. This will allow us to assure adequate seating and will also provide us with your contact information in the event that the program is cancelled due to weather. (To register, email to JLBCONEW@gmail.com with your name and the number of people attending.)

Other Observations

Animals on Ice

With the deep freeze across the Northeast and Midwest, coyotes from the Ohio River to Central Park to the Great Sippewissett Marsh (above left) have been spotted using frozen water bodies as travel routes. Crows also gathered en masse on Long Pond in Falmouth, MA. I looked up why crows gathered in large groups on ice and some of the thinking is that they have better lines of sight for potential predators (plus strength in numbers), and sitting on the ice can actually be warmer than sitting in windy trees. It looked like a solid hang.

You don’t always have to see the mushrooms to see the presence of fungi. This tree is growing large burls with dozens of little branches popping out of them in what looks like a response to some unseen infection, potentially fungal, but also possibly viral or bacterial.

These burls are created by hyperplasia, the creation of more xylem cells (the cells the tree uses to bring water from the roots to the branches and leaves). Note the difference in hypertrophy, which is the swelling of cells — something that bodybuilders are trying to achieve, and hyperplasia, the increased production of cells, something this white oak is using to combat an unknown pathogen.

One last observation was that both sides of the bike path Hank and I frequented were covered with invasive plants. This was also the case with both sides of the train tracks that bisected the preserve where I used to work, Manitou Point Preserve. The construction of roads and train tracks creates a blank canvas for fast-growing, potentially allelopathic, invasive species to move in and create a monoculture.

Above, we have black locust trees (Robinia pseudoacacia), a near-native that is found naturally in the southern Appalachians and Ozarks. They were actually brought north for their rot-resistant lumber. Above, they serve as a trellis for the fast-growing, tree-constricting oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus).

One would typically look at that scene, an invasive plant using a different invasive as a trellis, and categorize it as ecologically unhealthy. However, there was an entire flock of robins (Turdus migratorius — I don’t imagine they got to choose their name) that took cover in the dense tangle of vines and branches to gorge on the berries produced by the bittersweet. They were benefiting from the habitat created by the two invasives. It’s hopeful to see native animals using invasive plants, but it is truly bittersweet because they’re also helping to spread the seeds of the invasive plant.

Well, I’m not sure how much Hank retained from all our finds, but I hope he learned at least something along the way. I know I sure did.

I’m going to have to get creative for next week’s fungus,

Aubrey

References:

maybe for the burls: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witch%27s_broom

I know Taphrina betulina is a thing for birch, not sure about the tree you showed