Turkey Tail Hunting

The Gilled Polypore (Trametes Betulina)

Good afternoon, friends,

Not only did the snow melt, but it also rained this past week. While that doesn’t create the best conditions for human morale in January, it does make for great winter mushrooming. I went out on Wednesday and I didn’t even make it out of sight of the road when I found a large, downed beech tree covered in mushrooms large and small. I spent the next ninety minutes slowly making my way around this network of dead wood, and while this foray left something to be desired in the step-count department, it was quite rewarding fungally.

The largest mushroom I found was a flush of the Gilled Polypore (Trametes betulina) on the main trunk of the downed beech. While turkey hunting season doesn’t open until May, Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor) hunting is open year-round for this conspicuous mushroom.

Fun Facts

This is the eighth species of Trametes that I’ve written about, and fortunately for us, it’s the easiest to identify. That’s because unlike all the other Trametes, which have round or oblong pores of various shapes and sizes, this mushroom has “gills” — those blade-like projections you typically see on cap and stem mushrooms. Technically, they’re not true gills. They’re actually just extremely elongated pores, but please don’t let that bog you down. If you call them gills, that flies in my book.

Like other species of Trametes, this mushroom is jam-packed with anticancer and antibiotic compounds. A study out of China found that an alcohol extract of the mushroom inhibited the growth of breast cancer cells by 83% (Reference 2). Another study found that a hot water extract, essentially making tea with the mushroom, proved effective in killing both harmful E. coli bacteria and the bacteria that causes some types of pneumonia (Reference 3).

There is also one documented case of Keratitis (an inflammation of the eye) caused by this fungus (Reference 4). It was treatable with an antifungal. This seems particularly uncommon, as there’s only one documented case in the history of the world, but I guess we’ll take the good with the bad.

A Confusing, Destabilizing Etymology

Typically, the etymology is the easiest part of these newsletters. It’s fairly straightforward to find the roots of these words and understand how they relate to the fungus. However, that could not have been further from the case with this fungus.

I’d always understood Trametes to mean “thin one” where tram- is “thin”, and the suffix -etes means “one who is”. This is a very common mushroom genus, so I’ve puppeted this information on many different mushroom walks, and I’ve heard other people say it as well.

Interestingly, that etymology appears online in some blog sources, but I couldn’t find any dictionary that confirms tram means “thin” (-etes does indeed mean “one who is”). In Latin, trames means “path” or “track”, and trama means “weft” (and if you’re like the author and didn’t know what a weft is, it’s a thread used for sewing). A crafty Scrabble word to keep in the back pocket.

According to one artificial intelligence platform, tramēs appears in the Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English dictionary (“the gold standard for classical Greek lexicography” as you already know) and notes that, in uncommon translations, it can mean “thin”. Typically, however, in Ancient Greek, trēma means “hole”. This makes sense as Trametes have plenty of holes (pores) from which they release their spores. That seems to be the most logical etymology at the moment.

This conundrum delayed the publication of the article. I had to sleep on it, truthfully. I’d written about Trametes several times before, and had always just taken that translation for granted without double checking. Truthfully, I’m still not even sure what Trametes means, and I have so many tabs open right now it’s simply unsustainable. My internet browser and I are at a breaking point. I couldn’t find anything in my field guides, either. If anyone has any more concrete information, please let me know.

If we really wanted to find out, the Swedish mycologist Elias Magnus Fries was the first to describe the genus in his 1836 book Epicrisis Systematis Mycologici, Seu Synopsis Hymenomycetum, and a contemporary publication is available online. $43.95 to be able to sleep at night seems like a no-brainer.

As an aside, in mycology, trama is the term used to describe the fleshy body of a mushroom. Not the cap, nor the spore-producing surface, but the interior of the mushroom. The flesh of the fungus. Perhaps it’s be related to that?

Before Trametes, the fungus was called Lenzites betulina and appears in many field guides as such. That genus is named after the 19th century German mycologist and naturalist, Harald Lenz. That was a little easier to substantiate.

The species name betulina means “of birch” and you might think “oh this mushroom grows on birch”, which it does, but it also grows on a variety of hardwoods. I usually see it on Oak or beech. So that name’s not very helpful either. We’re going to leave the etymology section with more questions than answers.

Ecology

I learned from Bill Yule, the Merlin of Mushrooms and longtime member of the Connecticut Valley Mycological Society, that this fungus can be parasitic on Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor), but the way the fungus parasitizes its host is fascinating.

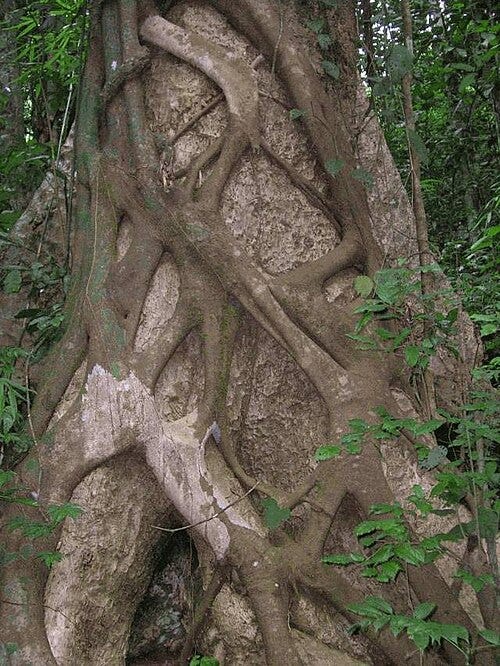

A 1986 study out of England looked at how Trametes betulina interacts with early decay fungi (the first fungi that get to recently colonized deadwood). They found that rather than leaching nutrients from the host, which is the mechanism for most fungus-on-fungus parasitism, T. betulina takes over the domain occupied by the host fungus — typically Turkey Tail (T. versicolor), but sometimes other species of Trametes. The researchers noted that the Turkey Tail’s “hyphae were seen to be tightly entwined and penetrated by narrow branches of L. betulina”, and they compared it to how a strangler fig strangles the host tree (Reference 5).

After colonizing the space formerly occupied by the Turkey Tail fungus, the Gilled Polypore turns into a decomposer that digests the lignin in the plant cell walls and leaves a spongy, white rot in hardwood.

T. betulina grows on all six major continents, and the range seems to be pretty similar to that of Turkey Tail (T. versicolor). The former doesn’t necessarily depend on its host to live, so I imagine it could be found on hardwoods that don’t have T. versicolor. There actually wasn’t any Turkey Tail on the log when I found it, but it’s hard to say it didn’t just push out and replace the Turkey Tail that was already living in the log. These “gilled” mushrooms pop up summer through fall and can persist over winter (which is why I found them in January).

A couple look-a-likes are the Mazegill polypore (Daedaleopsis confragosa) and the Oak Mazegill (recently renamed to Fomitopsis quercina), pictured below.

Bob Weir died on Saturday evening and Earth lost a good one.

I appreciate his own perspective on the passing. He said, “I look forward to dying. I tend to think of death as the last and best reward for a life well-lived. That’s it.”

That’s it indeed, those are some words to live and die by. I’ll be in his hometown of San Francisco later this week on the way to the Sonoma Mycological Association’s annual foray: SOMA Camp. It’ll be my first time in Northern California so the vast majority of those mushrooms will be new to me. Tune in next week to see what we find.

Until then, may the four winds blow you safely home,

Aubrey

References:

Kuo, M. (2024, March). Lenzites betulinus. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/lenzites_betulinus.html

Liu K, Wang JL, Zhao L, Wang Q. Anticancer and antimicrobial activities and chemical composition of the birch mazegill mushroom Lenzites betulina (higher Basidiomycetes). Int J Med Mushrooms. 2014;16(4):327-37. doi: 10.1615/intjmedmushrooms.v16.i4.30. PMID: 25271861.

Udeh AS, Ezebialu CU, Eze EA, Engwa GA. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity of Different Extracts of Some Wild Medicinal Mushrooms from Nigeria. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2021;23(10):83-95. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.2021040197. PMID: 34595894.

Hardin JS, Sutton DA, Wiederhold NP, Mele J, Goyal S. Fungal Keratitis Secondary to Trametes betulina: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Mycopathologia. 2017 Aug;182(7-8):755-759. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0128-6. Epub 2017 Mar 21. PMID: 28324243.

A.D.M. Rayner, Lynne Boddy, C.G. Dowson, Temporary parasitism of Coriolus spp. by Lenzites betulina: A strategy for domain capture in wood decay fungi, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, Volume 3, Issue 1, February 1987, Pages 53–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02338.x

The etymology section of this article reminds me of the chapter i wrote on turkey tail. In general, trametes seems to send people on a wild turkey chase. Haha

On another note, you'll probably see lots of these in northern California, because I just did.

I'm envious, but happy for you, that you'll be attending SOMA, I was just at CYO camp for a meditation retreat and its beautiful.

I wanted so badly to stay for this event, it looks incredible! But looking forward to reading about it and will attend next year!

The strangler fig parallel is brilliant. It's wild how T. betulina doesn'tjust feed on turkey tail but physically takes over its space through entwining. Makes you wonder if competition for territory matters more than nutrients in fungal succession. I spent way too much time last winter trying to distinguish these from regular turkey tails before realizing the gills were the obvius giveaway.