Toadstool Tuesday

Teal Conifer Pin (Dendrostilbella smaragdina) and the Mary Banning Exhibition

Good evening, friends,

This week’s mushroom comes from the same walk as last week’s Stereum, but this one required a bit more investigative work to discover. This time of the year in particular you may need to squint your eyes a little harder, possibly roll over a log or two, and that’s how we stumbled on the teal conifer pin (Dendrostilbella smaragdina). This mushroom may be hard to see, but it’s quietly providing some interesting and important ecological benefits.

I also got up to Albany on Friday to see our friend Patty and the opening of the Mary Bannon exhibition which I’ll detail a bit below.

Fun Facts

There isn’t much formal research on these tiny little pins, but they did pop up in one agricultural study that looked at the effects of no-till agriculture (the practice of not turning over the soil in the spring) on grain yields. The researchers found that no-till practice (combined with the top-dressing of manure) was not only the best practice for crop yields, but this method also resulted in a boom in the diversity of soil fungi. In particular, they noticed a large increase in the abundance of Dendrostilbella (Reference 1).

Some fungi are considered Plant-Growth-Promoting-Fungi (PGPF). In fact, th fungus from which Penicilin is derived (Penicillium) is considered a PGPF species. In the soil, PGPF form an association with plant/crop roots to help with nutrient uptake, disease resistance, and other mechanisms that all result in increased plant growth and crop yield. No-till allows for denser mycelium to form which strengthens both plant and fungal health, and evidently Dendrostilbella is one of these PGPF species that benefits.

Dendrostilbella is a mouthful but makes sense when we untangle the roots of the word. The prefix Dendro- comes from the Greek dendron and means tree or tree-like, and in this instance probably refers to the erect structure of these mushrooms. The remaining pieces can be deciphered as stil, from the Greek “stilos” which means “columns”, and the suffix -bella means “small”. The genus translates to “small, tree-like columns” and aptly describes the shape of the mushroom.

The species epithet smaragdina comes from the Greek smaragdos, which means “emerald”, and refers to the color of the mushroom. The emerald orbs you see at the top of the small, black stems are actually liquid spore matter. The liquid evaporates and the spores float off into the atmosphere.

Ecology

A lot of fungi can occupy different ecological roles at different stages in their life. For example, all mycorrhizal fungi are decomposers (saprobes) before they find a plant partner to form a nutrient exchange. Dendrostilbella smaragdina is no exception with the ability to form relationships with plants but also act as a decomposer on conifer wood. I imagine environmental pressures and availabilities determine how the fungus lives, but more research is needed to determine this with certainty.

The fungus has limited observations on Mushroom Observer and iNaturalist, but so far these tiny emerald pins have only been found in Europe and North America. They seem to be found almost any time of the year after rain on saturated conifer wood. It also looks like the mycelium of the fungus discolor the wood, similar to the effect Chlorociboria has but on a much smaller scale.

The fruiting bodies you see below are actually the anamorph of the fungus, the asexual reproductive structures. The teleomorph, the sexual reproductive stage of the fungus, is unknown.

Outcasts: The Mary Banning Exhibition Opening Reception

On Friday evening I joined the Catskill Fungi crew as we carpooled up to Albany for the opening reception of Outcasts: Mary Banning’s World of Mushrooms at the New York State Museum. It was fun to see a lot of mushroom people in one place — I believe there were over 200 people in attendance over the course of the evening.

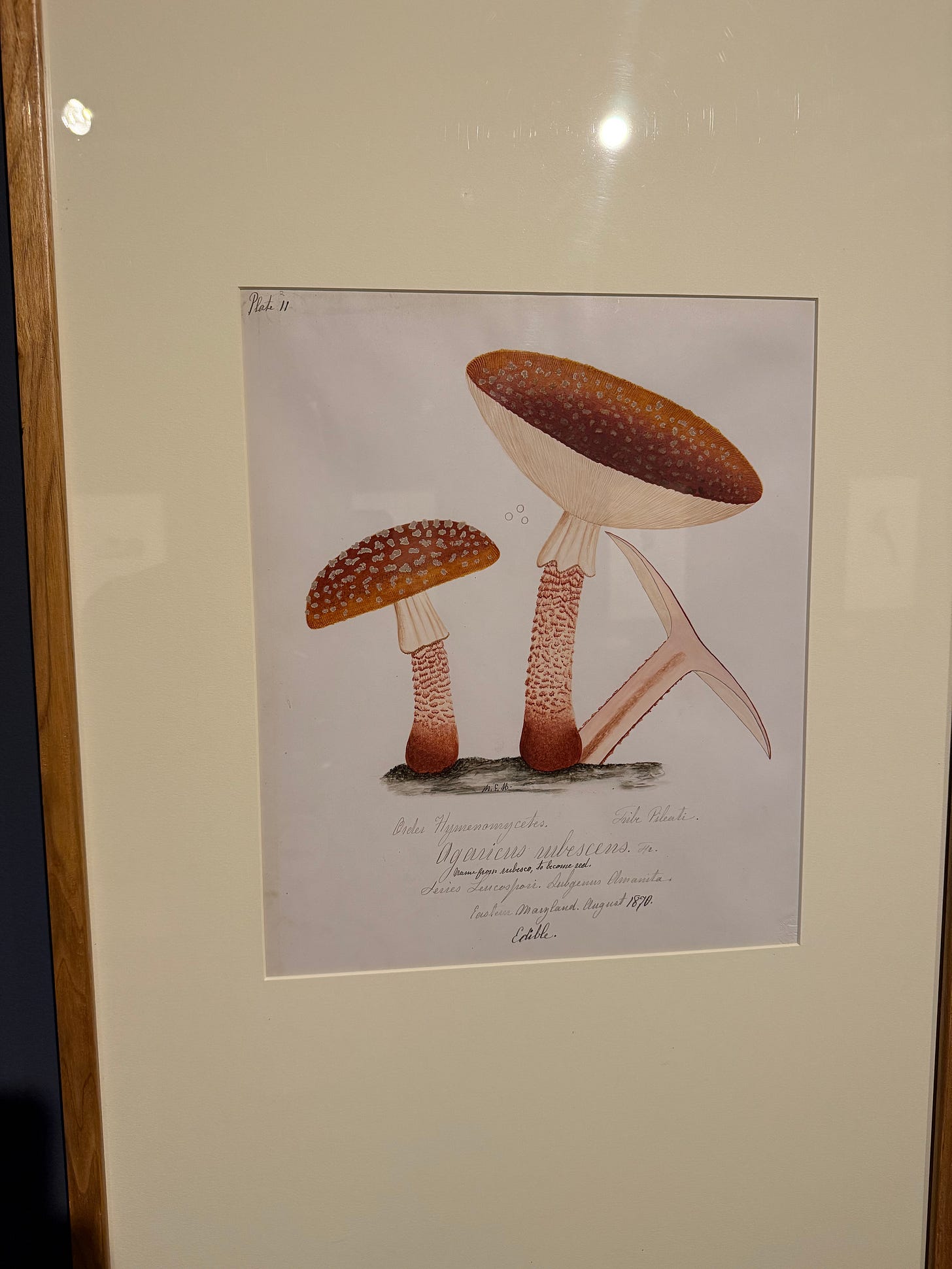

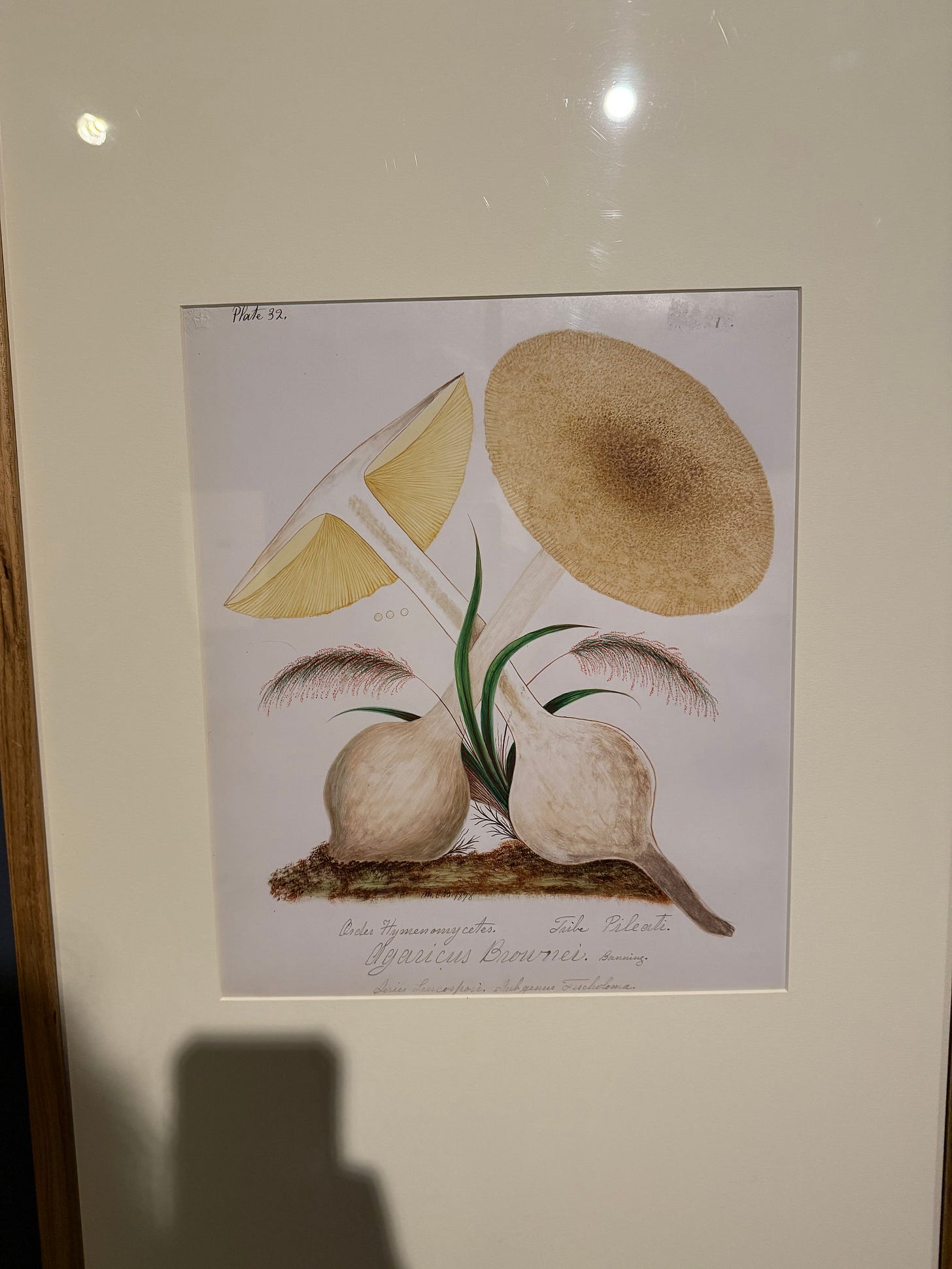

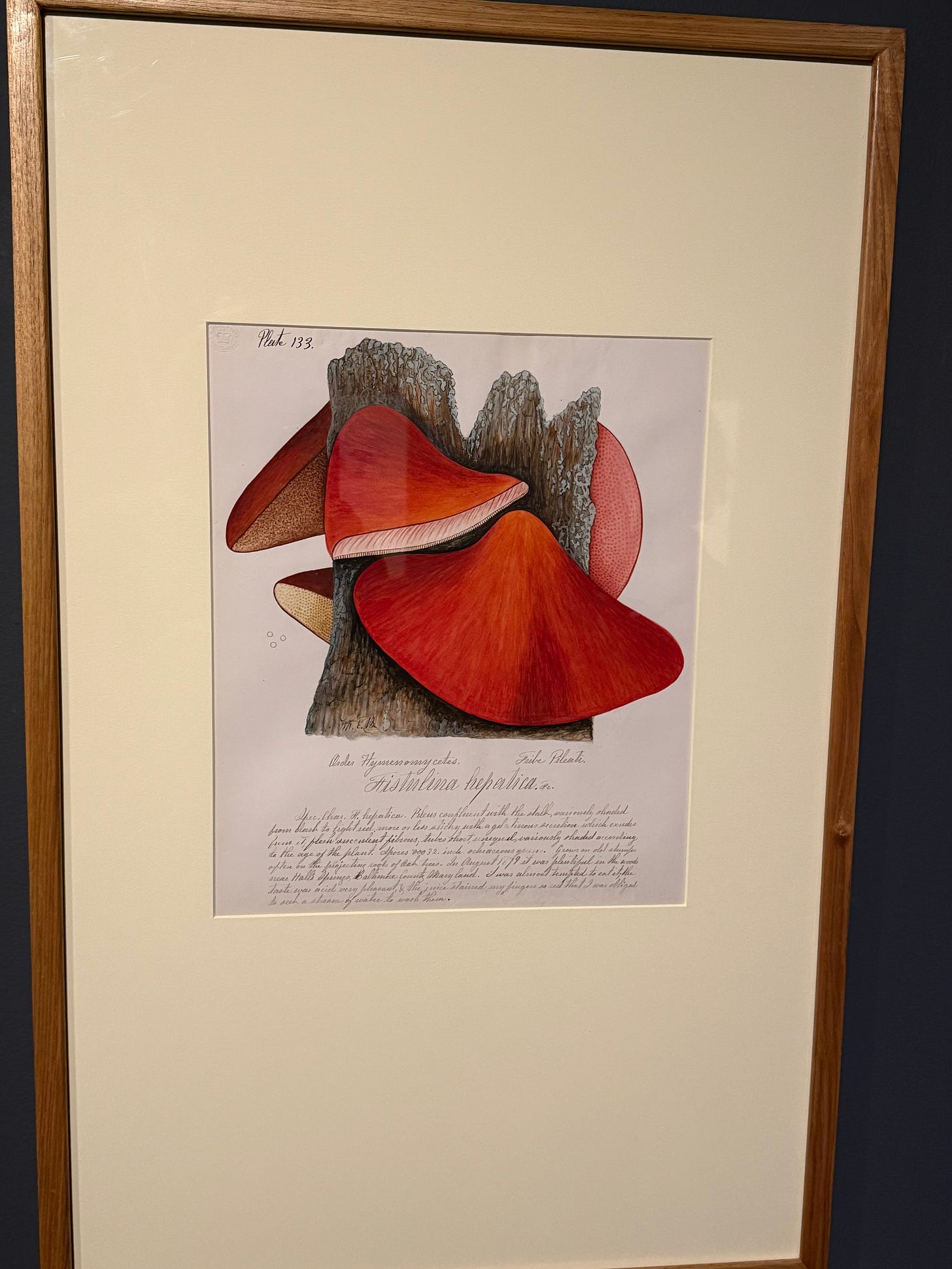

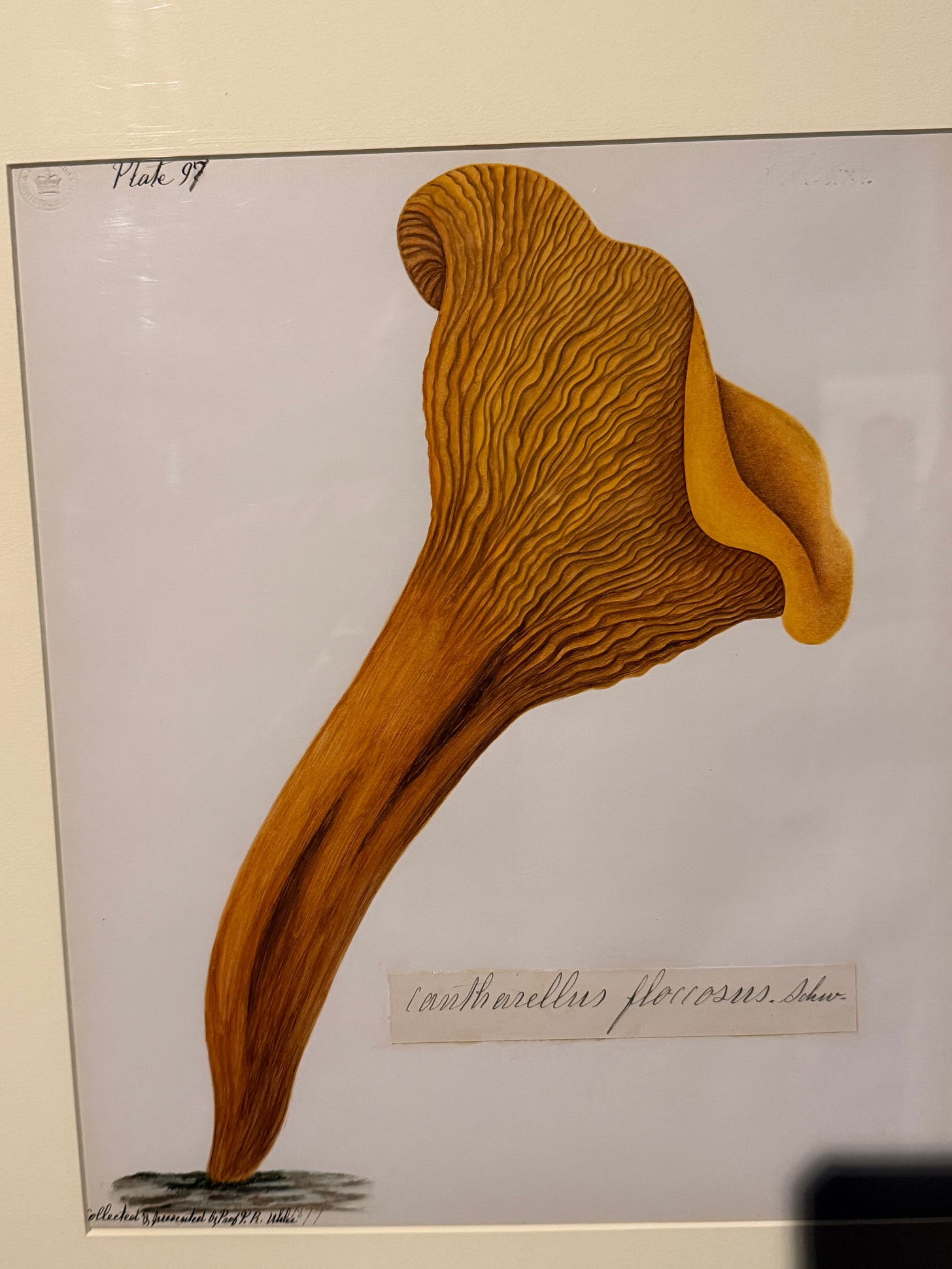

Mary Banning was a 19th century mycologist and illustrator from Baltimore, Maryland. At a time when botany and mycology were fields dominated by men, she was a pioneer, and she subsequently became the first woman outside of Europe to describe a new fungal species. She is finally receiving some appreciation with this exhibition which features dozens of Banning’s mycological illustrations as well as other interesting fungal forms.

Throughout her career, Banning described twenty-three species new to science. Along the way, she established a working relationship with the renowned mycologist Charles Peck, the New York State botanist (mushrooms were considered plants) from 1868 to 1913.

With deep admiration and appreciation for Peck, she decided to send him her life’s work, the manuscript of The Fungi of Maryland, with the hopes that he would use his position and resources to have it published. The manuscript, now on display, consists of thorough descriptions and beautifully illustrated watercolors of mushrooms Banning found in her home state. Unfortunately, Peck didn’t seem too interested in doing anything with these illustrations other than tucking them in a filing cabinet in the recesses of the museum.

Banning, in one of her letters, described how she deeply regretted parting with the work and now felt that a part of her was missing. A snippet of the letter correspondence between her and Peck, at least my paraphrasing of it, went something like this:

Banning: Charles, I do hope you received my manuscript. I regret ever separating from it. I have a deep longing to be with my work once again, and my heart aches every day I’m without it.

Peck: Hey Mary, yea I got the pictures, looks good. I have a new book being published, would you be interested in a copy?

Mary died in 1903 without ever receiving assurance or acknowledgement that her work would have a lasting impact on mycology. It wasn’t until 1979 when John Haines, the New York State museum’s curator of mycology at the time, unearthed these works for the world to see. He was able have them displayed for the public as part of a traveling exhibition, and he even wrote a play based on the letter correspondence between Banning and Peck.

However, these delicate watercolors can diminish with extended exposure to light, so after their brief tour they were tucked back in the dark for decades. That was until the current curator, Patty Kaishian, assembled them for this new exhibition on Banning that runs through the end of the year.

Of additional interest, the exhibit features a fossilized prototaxite which dates back to around 380 million years ago. Prototaxites are thought to be a large, extinct, fungal fruiting body that dates back to a few hundred million years ago. At the time, they were thought to be the largest terrestrial organisms on the planet and could grow over 20 feet tall.

Of course, a new study contends that these prototaxites were not fungal and instead belong to an extinct branch of life. As it turns out, it’s hard to determine who was what four hundred million years ago. Regardless, I found it special to even be in the same room as this wise elder.

It’s a charming exhibition that puts the focus on Mary Banning and fungi (for once). The illustrations are delicate (she even includes the mushrooms’ spores which is a thoughtful addition) and the other fungal features on display are fascinating. If you find yourself in Albany it’s a can’t miss.

Full moon on Saturday,

Aubrey

References:

Chen M, Yang H, Yang Q, Li Y, Wang H, Wang J, Fan Q, Yang N, Wang K, Zhang J, Yuan J, Dong P, Wang L. Different Impacts of Long-Term Tillage and Manure on Yield and N Use Efficiency, Soil Fertility, and Fungal Community in Rainfed Wheat in Loess Plateau. Plants (Basel). 2024 Dec 12;13(24):3477. doi: 10.3390/plants13243477. PMID: 39771175; PMCID: PMC11677417.

https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/518862-Dendrostilbella-smaragdina

https://www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/collections/mary-banning-fungi-of-maryland

https://fungi.myspecies.info/taxonomy/term/9592/descriptions

Mary Banning put in some work!

I enjoyed this find , Aubrey. Thanks.