Powder Cap Parasites

The Curious Case of Asterophora lycoperdoides

Good evening, friends,

If you haven’t been outside the past month, it’s been cold. And despite snow lingering on the ground, the air is pretty dry. Not the most conducive to fungal growth. I went out a couple times last week and found a few crusts that I want to take a closer look at, but I’m hoping for more action when the snow melts later this week.

Meanwhile, as I continued to look at the DNA results which I wrote a bit about last week, I was reminded of a mushroom from the fall that I didn’t get a chance to highlight. Well, two mushrooms, actually. The idea of waiting until next fall to write about them was unappealing, so that’s why today we get to learn about the Powder Caps (Asterophora lycoperdoides) we found in October at the Breivogel Ponds Conservation Area in Falmouth, MA.

Fun Facts

A bunch of the mushrooms we look at grow on wood, tons grow from the soil, but rarely do we look at mushrooms that grow out of mushrooms. Off the top of my head, I can name a handful that exist: the parasitic bolete (Pseudoboletus parasiticus), which grows from an earthball (Scleroderma), and the piggyback shanklets (Collybia cirrhata) which I found in the Adirondacks. There are also two mushrooms in the Northeast Rare Fungi Challenge (Volvariella surrecta and Psathyrella epimyces) that fruit out of or “piggyback” off of other mushrooms.

Those four aside, most basidiomycetes are not parasites, and the majority of parasitic fungi are in different phyla entirely. Cordyceps, like the zombie ant fungus, are ascomycetes, and the fungus responsible for chytridiomycosis, which has devastated amphibian populations across the world, is in the phylum Chytridomycota.

Another quirk of A. lycoperdoides is that the fungus is capable of both asexual, clonal reproduction and sexual reproduction from two genetically distinct individuals. The ability of fungi to reproduce sexually and asexually, typically seen more in ascomycetes, is one of my favorite aspects of fungi. It’s evolutionarily advantageous to be able to both clone yourself, and recombine your DNA with other mating types in your species — these fungi are no stranger to pleasure as they get to enjoy the best of both worlds.

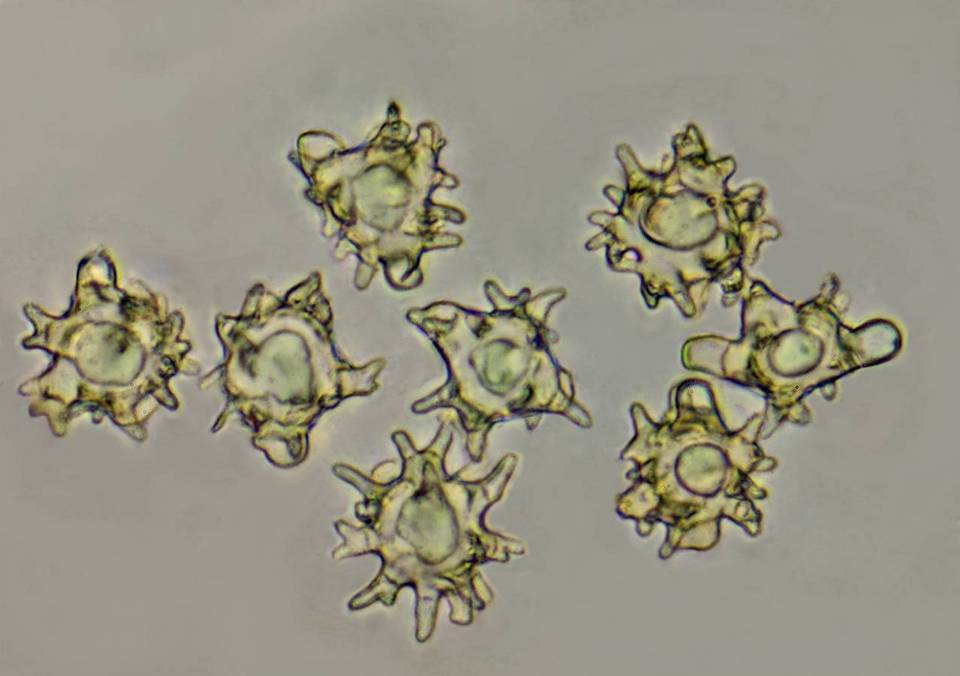

The brown powder on the caps of these parasitic mushrooms is actually the asexual spores, known as chlamydospores. They’re not considered “true spores” by those that consider spores because they’re not formed under the normal spore-producing pathways. These chlamydospores form from swollen ends of hyphae, the regular body of the fungus, not from any specialized fruiting structures like true spores. It’d be comparable to if our fingernails swelled, fell off, and turned into little clones of ourselves.

These chlamydospores have thick walls that prevent them from drying out, and they are shaped like underwater mines. They’re designed to persist dormant in the environment for long periods of time. The fungus will also produce sexual spores, albeit not nearly as many, through the gill-like structures under the powdery cap.

Etymology

The name Asterophora is derived from the Greek astér, which means “star”, and the suffix -phora comes from the Greek phoréo, which means “to bear”. This is a star-bearing moniker is a reference to the star-shaped chlamydospores produced by the fungus. The species lycoperdoides means that it is “Lycoperdon-like”, or “like a puffball”. While there’s no taxonomic relation to puffballs, the mushroom does look like an inside-out puffball with all of the powdery brown spores forming on the outside of the mushroom.

The fungus used to be named Nyctalis asterophora, the genus denoting “of the night”. This seemed to be a nod to the mushroom’s mysterious appearance out of dark, desiccated mushrooms.

Ecology

A. lycoperdoides is parasitic on mushrooms in the family Russulaceae, which include brittlegills (Russulas) and milkcaps (Lactarius). We found ours on a black-staining Russula, Russula dissimulans, and the powder caps were on nearly every old R. dissimulans in the area. These little parasites grow summer through fall in temperate forests of the northern hemisphere wherever their host species are found.

The host Russula dissimulans is a large, white Russula that bruises red, but then that red fades to black. When the mushrooms are older, they turn all black, and that’s when the powder caps pop up.

It’d be one thing if they were aborting mushrooms that never had a chance to form and release spores, like what the aborted entoloma does to honey mushrooms, but these were only growing out of mushrooms that had their best days well behind them. It makes me wonder how disruptive they actually are, if at all, to their host’s life cycle.

The DNA confirmation of this species was helpful to confirm which species we have on the Cape, but to our knowledge, there are only two species in the genus Asterophora. A coin-flip from the jump. Better yet, the two actually appear to be distinguishable in the field. The sister species, Asterophora parasitica, doesn’t produce the powdery chlamydospores on the cap and also has fully developed gills.

Alright, well that puts a bow on what is notoriously a tough Monday. The holiday fun is over and it’s back to reality. At least the days are getting longer,

Aubrey

References:

Kuo, M. (2020, October). Asterophora lycoperdoides. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/asterophora_lycoperdoides.html

https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/150-asterophora-lycoperdoides/

https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/125378-Asterophora-lycoperdoides

Wow. I like the effort that you put in these posts. Thank you so much! I also like fungi! I used to be fascinated about fungi since I was a little kid. If your interested, please check out my channel (I post about astronomy) and subscribe!

Enjoyed the informative post. Met my myco proximal zone of development. I have a question, don't know if you can answer it, might be related and might not: butyriboletus brunneus has, if I understand correctly, hyphae in the tubes, stuffed pores. Can you explain why, and is it related to spores generated on the end of hyphae described above?