Good evening good people,

This week’s mushroom is the Emerald Elfcup (Chlorociboria spp.) - the spp means “species”. Not only were these little jewels popping during Mycofest, but I found some fresh fruiting bodies up in Manitou this past week as well. If you walk in the woods any time of the year on any continent in the world (besides Antarctica, as long-time readers know tends to be the case) you may stumble upon some dead wood colored a deep turquoise. One of the first pictures on my phone is a piece of blue wood from February 2017 when I had the privilege of asking a great naturalist, Ted Gilman, the simple question of why the wood was blue. He explained that it was the mycelium of a fungus in the wood that created the color, and six years later I’m happy to elaborate a little more about this natural oddity.

Fun Facts

Technically, it’s an opinion that this is one of the most aesthetically appealing fruiting bodies in the wide world of fungi, but it feels like fact. And when the ephemeral fruiting bodies aren’t around, people have been using the greenish-blue wood in varying ways throughout history. The 1800s in Kent, England saw people use Chlorociboria stained wood to create “Tunbridge ware”, a style of woodworking which congealed different colored pieces of wood to create anything from paper weights to musical instruments. Researchers have also shot lasers at “one of the intarsia panels of the Gubbio studiolo” (a 15th century Italian painting housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and determined that the mycelial growth and pigments in the wood are consistent with Chlorociboria (Reference 3). Pretty impressive.

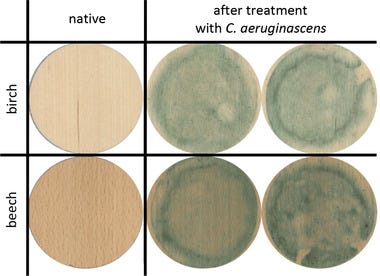

You may also be wondering if this charismatic color can be used for dyeing textiles, and fortunately for us many scientists have wondered the same. Xylindein is the specific compound in the fungus that stains the wood turquoise. A 2021 study from Germany found that Chlorociboria aeruginascens could be cultivated in a lab setting. They were able to produce 70 liters of a liquid culture (the fungus growing in a sugary broth) and then dyed wood in as little as three months where prior experiments took over two years (Reference 4). The same researchers also found that chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) was a potent dye for silk and they offer up both of these fungi as practical, commercially-viable, and eco-friendly alternatives to the often hazardous synthetic colorants.

There are at least two species of Chlorociboria in the northeast: Chlorociboria aeruginascens and Chlorociboria aeruginosa, and they’re essentially identical to the naked eye. To further complicate things, in 2014 the British Mycological Society tried to give common names to every fungus and named C. aeruginascens the “Green Elfcup” while C. aeruginosa is the “Turquoise Elfcup”. With almost identical latin and common names for already identical species, I split the middle and decided to use the name “Emerald Elfcup” to describe these specimens. If you couldn’t tell, I like alliteration.

I didn’t have the privilege of hearing him say it in person, but it’s been intimated to me that Gary Lincoff emphasized the name is not nearly as important as the mushroom itself, and what the fungus/mushroom is doing in the world :). If you’re really curious, you can compare spores here - it appears that those of C. aeruginosa are larger.

Ecology

The fungus is saprobic, decomposing dead wood of both hardwoods and conifers. I tend to see it on birch a lot in the woods in and around NYC, but online sources say that it has a penchant for oak. It’s likely different species have different food preferences. The stained wood can be found year-round, but the fresh fruiting bodies are found during/immediately after rain in the summer and fall. Just hours after placing the specimen on the identification table at Mycofest, people were puzzled as to what on the branch they were supposed to look at after the cups had dehydrated to an almost sub-perceptible size. The fruiting bodies start as small cups and then flesh out into discs, but still don’t get much larger than a few millimeters across.

The fungus is an ascomycete so instead of relying on gravity like most of the basidiomycetes we look at, spores develop internally and are ejected out of sac-like asci. There aren’t too many look-a-likes but there is Dendrostilbella smaragdina (below) which was found during the NYMS walk up in Manitou. These produce a similar colored wood but are pin-shaped and even smaller.

It’s going to rain tonight into tomorrow morning so it’s the perfect opportunity to find these cerulean saucers on your own. Good luck,

Aubrey

References:

Kuo, M. (2015, May). Chlorociboria aeruginascens. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/chlorociboria_aeruginascens.html

Blanchette, Robert & Wilmering, Antoine & Baumeister, Mechthild. (1992). The Use of Green-Stained Wood Caused by the Fungus Chlorociboria in Intarsia Masterpieces from the 15th Century. Holzforschung. 46. 225-232. 10.1515/hfsg.1992.46.3.225.

Zschätzsch M, Steudler S, Reinhardt O, Bergmann P, Ersoy F, Stange S, Wagenführ A, Walther T, Berger RG, Werner A. Production of natural colorants by liquid fermentation with Chlorociboria aeruginascens and Laetiporus sulphureus and prospective applications. Eng Life Sci. 2021 Jan 26;21(3-4):270-282. doi: 10.1002/elsc.202000079. PMID: 33716624; PMCID: PMC7923565.

https://www.first-nature.com/fungi/chlorociboria-aeruginascens.php